Training student doctors to become educators

Aimee Charnell, Laura Stephenson & Michael Scales

Cite this article as: BJMP 2018;11(1):a1103

|

|

Abstract Introduction: Doctors are expected to teach from a very early stage in their foundation training, often without prior formal instruction in clinical teaching skills. We provided a course with an aim of providing newly qualified doctors with the skills to teach students and peers. Methods: We developed two, half day courses which ran over subsequent years, addressing feedback from the first course to allow improvement. Sessions included Teaching Theory, Teaching Your Peers and Teaching for Your Learning and Portfolio, with small group discussions also incorporated into the second course. Results: Results from the second course showed 100% of delegates rated each individual session either ‘Good’ or ‘Very Good’. 70% felt that this day should be compulsory for all new doctors. Delegates were contacted six months into their foundation posts for further, reflective feedback. Of 14 responses, 100% felt this course should be delivered again and all respondents felt more confident in teaching compared to their peers. Conclusions: We propose that formal education in Clinical teaching should be provided to students at undergraduate level. We suggest this could be made a compulsory part of the curriculum or during hospital inductions or at least offered as student selected components. Keywords: education, training, teaching, simulation |

Introduction

Within the United Kingdom, all doctors are expected to teach.1 It is assessed throughout their professional career, during annual appraisals for doctors in training and during consultant revalidation. But how are those just embarking on their medical career expected to develop the necessary teaching skills? As three educators at various stages in our clinical careers, we developed and delivered a small course with the aim of addressing this issue.

The General Medical Council within the United Kingdom, suggest that a basic comprehension of teaching should be gained during the undergraduate and postgraduate training of doctors.2 Dandavino et al. further suggest that early development of these teaching skills may have additional benefits for the clinician; such as improving communication and assisting undergraduates to develop their own ability to learn.3 Our local training region, Yorkshire and the Humber Deanery (HEYH), have a mandatory post-graduate training day in teaching skills which focuses on generic and clinical teaching skills. This is delivered towards the end of the first foundation year. It is delivered by doctors who have various roles in medical education. Whilst useful in its content, for many it comes late. Doctors have often already been involved in providing teaching to medical students on placement at this time.

AMC recalls from her first postgraduate (foundation) year. One peer was thrilled to have ‘shaken-off’ a final year medical student who was supposed to accompany them on a shift as a learning experience; stating that they were now able to ‘do some work’. She couldn’t understand the desperation to escape one-to-one teaching. On reflection, it was probable that her colleague found it overwhelming to incorporate the additional responsibility of teaching alongside an already stressful clinical workload. Many share these feelings, with new doctors finding time pressures along with competing clinical demands a challenge to implementing clinical teaching.4

We thought that giving our graduates simple tools to understand and overcome these challenges may empower them as teachers. It may also improve their confidence in other areas, such as in their own learning and presentation skills.5-6 This paper proposes a solution; after creating a short course to be delivered immediately following graduation, to empower new doctors as teachers by providing some basic training in clinical teaching. These doctors are then able to use this training as soon as they begin their foundation training, which is ultimately the beginning of their teaching career.

Methods

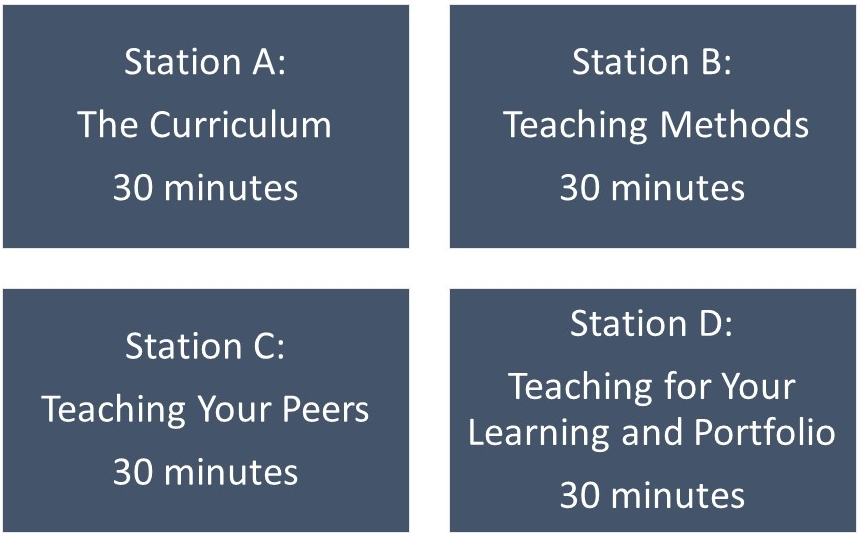

Two versions of a half-day course, titled ‘Teach the Medic’ were developed in HEYH which ran in successive years. The original course was designed by a surgical trainee (AMC) and a general practitioner running the undergraduate education curriculum (MS). Initial topics were chosen based on experiences of the authors and colleagues. The optional course (see figure 1), was offered to the cohort of Leeds medical students who were in the transition period between finishing their final examinations and commencing their first post as a doctor.

Figure 1: A representation of the initial course structure. Stations were developed as interactive lectures and delivered to participants by doctors of various training levels.

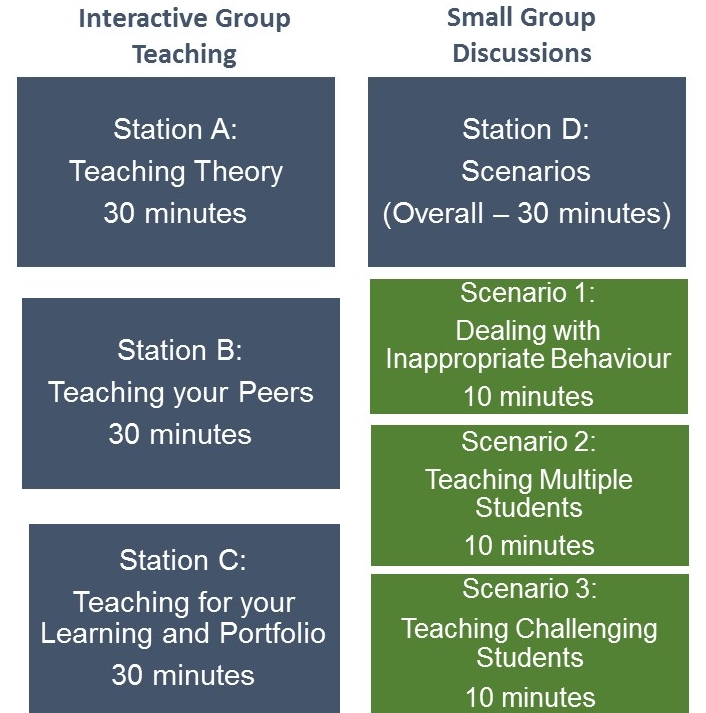

The initial course received encouraging verbal and written feedback from the participants, which was collected on the day of the course. Further feedback was collected a few months into foundation training, allowing enough time to pass for delegates to use this knowledge. This feedback, whilst encouraging, included that delegates were keen for additional workshop style sessions. Subsequently, a modified half-day course ran the following year, with the recruitment of additional postgraduate teachers (including LES). A further 17 newly qualified doctors from various medical schools completed the course, prior to commencing their HEYH foundation post. This modified course (see figure 2) included scenario based sessions around potentially difficult situations for the clinical teacher, and also explored alternative styles of teaching that could be adopted successfully in the workplace.

Figure 2: A representation of the modified course structure. Building on feedback from the initial course, the three co-authors incorporated new small group scenario based discussions, alongside the interactive lectures.

Results

Initial feedback received from evaluation of the day was positive for both courses. For the second course, initial feedback found that all participants found every session very good (71%) or good (29%) overall. 12/17 (71%) thought that the course should be made compulsory to medical students. We also sent a follow-up survey, distributed six months after the course which generated 14 responses. All respondents felt that the course should be run again. All participants either strongly agreed (n=2, 14%) or agreed (n=12, 86%) that they felt more confident in teaching compared with their peers. Regarding individual sessions, 10 participants (71%) had directly incorporated learning from the ‘Teaching Theory’ session, 12 (86%) from the ‘Teaching for your Learning and Portfolio’ session, 11 (79%) from the ‘Teaching your Peers’ session, and 10 (71%) from the ‘Scenarios’ workshop. All participants stated they would still recommend this course to colleagues. They also reported directly incorporating their learning from the sessions into their teaching practice. The responses gathered from the second course implied that participants felt more confident in teaching when compared to their peers.

Discussion

We feel the course content in ‘Teach the Medic’ complements other courses available later in one’s career, such as the Royal College of Surgeons’ ‘Train the Trainer’ course. We propose this course could be run by a junior doctor who has a strong interest in clinical teaching with involvement of a senior colleague with extensive medical education experience. We felt the course was especially beneficial as participants had continued to find it useful long after its delivery.

To expand this project to include a whole year group as a compulsory course is ambitious. It would require development and the use of more resources, but initial feedback suggested participants will find it extremely useful. Bing-You et al.6 agree, having found that undergraduate students would be willing to undertake formal instruction in clinical teaching prior to graduation.

As our short course gains momentum within HEYH, this prospect becomes more achievable. When considering a wider delivered course, one must remember that attendance to ‘Teach the Medic’ was optional; suggesting that those who attended had already identified an interest in teaching. This has the potential to bias our data to some degree. However, we still believe that making the session compulsory would allow skill development and empowerment for those who may not consider themselves aspiring medical educators, but who are still in positions to deliver teaching.

Conclusion

Our evolving teaching skills course suggests that close work with both local medical schools and deaneries is important to allow this course to be incorporated into the training of newly qualified doctors. This may be included as a compulsory part of the final year medical school curriculum, an option for a SSC, or as an integrated part of the new starter induction programme delivered by individual hospitals.

|

Acknowledgements N/A Competing Interests None declared Author Details AIMEE CHARNELL, BSC, MBCHB, MRCS (ENG), PG CERT., University of Leeds, School of Medicine. UK. LAURA STEPHENSON, BSC, MBCHB, PG CERT. University of Leeds, School of Medicine. UK. MICHAEL SCALES. MBCHB, PG CERT, Clinical Lecturer. University of Leeds, School of Medicine. UK. CORRESPONDENCE: AIMEE CHARNELL, Via Learning and Teaching Office, Level 7, School of Medicine, University of Leeds, LS2 9JT Email: aimee.charnell@doctors.org.uk |

References

- General Medical Council. Good Medical Practice. London: GMC, 2013

- General Medical Council. Developing teachers and trainers in undergraduate medical education. London: GMC, 2011

- Dandavino M, Snell L, Wiseman J. Why medical students should learn how to teach. Med Teach. 2007;29(6):558-65

- Spencer J. ABC of learning and teaching in medicine. Learning and teaching in the clinical environment. BMJ. 2003;326:591-4

- Hill AG, Srinivasa S, Hawken SJ, Barrow M, Farrell SE, Hattie J, Yu T. Impact of a resident-as-teacher workshop on teaching behavior of interns and learning outcomes of medical students. The Journal of Graduate Medical Education. 2012;4(1):34-41

- Marton GE, McCullough B, Ramnanan CJ. A review of teaching skills development programmes for medical students. Med Educ. 2015;49:149-60

- Bing-You RG, Sproul MS. Medical students’ perceptions of themselves and residents as teachers. Med Teach. 1992;14(2-3): 133-8

The above article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.