Shazia Tabassum Hakim, Samina Noorali, Meaghen Ashby, Anisah Bagasra, Shahana U. Kazmi and Omar Bagasra

Abstract

Background: Both Hepatitis B virus (HBV) and Hepatitis C virus (HCV) are aetiological agents of acute and chronic liver disease existing throughout the world. The high genetic variability of HBV and HCV genome is reflected by eight genotypes (A to H) and six genotypes (1 to 6), respectively. Each genotype has a characteristic geographical distribution, which is important epidemiologically. Previous studies from the province of Sindh, Pakistan have reported that genotypes D and A as well as D and B are prevalent HBV genotypes, and for HCV genotypes 3a and 3b to be dominant. The aim of this study was to investigate the prevalence of co-infection of both HBV and HCV genotypes in physically healthy females at two universities in Karachi, Sindh, Pakistan and HBV diagnosed patients41,42,56-59.

Methodology: Blood was collected from a total of 4000 healthy female volunteer students and 28 HBV diagnosed patients. Serum samples obtained were screened for Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), anti-HBs antibodies and anti-HCV antibodies by immunochromatography and ELISA. Genotyping was carried out for 6 HBV genotypes (A through F) and 6 HCV genotypes (1 through 6). Genotyping data of HBV and HCV positive individuals are described.

Results: Out of 4028 volunteers, 172 (4.3%) tested positive for HBsAg. All 172 serum samples were genotyped by PCR for both HBV and HCV. Out of 172 HBsAg positive samples, 89 (51.7%) showed a single HBV genotype D infection, followed by genotypes A (6.4%), F (4.6%), B (3.5%), E (1.7%), and C (1.7%). Out of 43 positive for HCV by PCR from the two universities and Anklesaria Hospital, 65.1% showed infection with 3a, followed by genotypes 5a (11.6%), 6a (11.6%), 3b (9.3%) and 2a (2.3%). Hence, the co-infection rate of both these viruses is 25% (43/172) among HBs Ag positive individuals.

Conclusion: Genotype D for HBV and genotype 3a for HCV appears to be the dominant genotype prevalent in Karachi’s population and co-infection of both these viruses does exist in HBsAg positive individuals.

Keywords: Hepatitis B virus, Hepatitis C virus, type-specific primer-based genotyping

|

Introduction:

Both Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) and Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) are diseases characterized by a high global prevalence, complex clinical course, and limited effectiveness of currently available antiviral therapy. Approximately 2 billion people worldwide have been infected with the HBV and about 350 million live with chronic infection. An estimated 600,000 persons die each year due to the acute or chronic consequences of HBV 1, 2. WHO also estimates that about 200 million people, or 3% of the world's population, are infected with HCV and 3 to 4 million persons are newly infected each year. This results in 170 million chronic carriers globally at risk of developing liver cirrhosis and/or liver cancer 3, 4. Hence, HBV and HCV infections account for a substantial proportion of liver diseases worldwide.

These viruses have some differences, like HBV belongs to the Hepadnaviridae family and HCV belongs to the Flaviviridae family. HBV has a circular, partially double-stranded DNA genome of approximately 3.2 kb, whereas HCV has a single RNA strand genome of approximately 9.6 kb. HBV and HCV show some common biological features. Both HBV and HCV show a large heterogenicity of their viral genomes producing various genotypes. Based on genomic nucleotide sequence divergence of greater than 8%, HBV has been classified into eight genotypes labeled A through H 5,6,7,8. Different isolates of HCV show substantial nucleotide sequence variation distributed throughout the genome. Regions encoding the envelope proteins are the most variable, whereas the 5’ non-coding region (NCR) is the most conserved 9. Because it is the most conserved with minor heterogeneity, several researchers have considered the 5’ NCR the region of choice for virus detection by reverse transcription (RT)-PCR. Sequence analysis performed on isolates from different geographical areas around the world has revealed the presence of different genotypes, genotypes 1 to 6 10. A typing scheme using restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of the 5’ NCR was able to differentiate the six major genotypes 11. Hence both HBV and HCV genotypes display significant differences in their global distribution and prevalence, making genotyping a useful method for determining the source of HBV and HCV transmission in an infected localized population 12 - 27.

Many studies have been conducted to study the prevalence of HBV and HCV co-infection among HIV-infected individuals and intravenous drug users globally 28 -3 4.There are only a few studies relevant to the epidemiology of these types of infection in the normal healthy population 35,36,37. The objective in this study was to determine the seroprevalence of HBV and HCV, co-infection of both these viruses and their genotypes, among an apparently healthy female population as well as from known HBV patients in Karachi, a major city in the province of Sindh, Pakistan. This study is also aimed at providing the baseline data on HBV/HCV co-infection, in order to gain a better understanding of the public health issues in Pakistan. We evaluated the antigen, antibody and genotypes of both HBV and HCV in 144 otherwise healthy female individuals and 28 diagnosed HBV patients.

Materials and Methods:

Study duration:From March 2002 to October 2006 & April 2009

Study participants: Total 4000blood serum samples were collected from healthy female student volunteers and 28 serum samples (April 2009) from already diagnosed Hepatitis B positive patients, aged 16 to 65 years from two Karachi universities and one Karachi hospital. University samples were obtained through the Department of Microbiology, University of Karachi and the Department of Microbiology, Jinnah University for Women. Hospital samples were obtained through the Pathological Laboratory of Burgor Anklesaria Nursing Home and Hospital.

Ethical Consent: Signed informed consent forms were collected from all volunteers following Institutional Review Board policies of the respective institutes.

Pre study screening:All 4028 volunteers had health checkups by a medical doctor before collection of specimens, they were asked about their history of jaundice, blood transfusion, sexual contacts, and exposure to needles, and if they had undergone any surgical and dental procedures.

Biochemical & Hematological screening:On completion of the medical checkups, volunteers were asked to give 5mL of blood for different haematological [(complete blood picture (CP), haemoglobin percentage (Hb%) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR)] and 10mL for different biochemical tests [(direct bilirubin, indirect bilirubin, total bilirubin, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and alkaline phosphatase (ALP)]. Serological analysis:Samples were also subjected to serological analysis for hepatitis B surface Antigen (HBsAg), HBs antibodies and HCV antibodiesusing rapid immunochromatography kits (ICT, Australia and Abbott, USA). Confirmatory test for HBsAg was done by using ELISA (IMX, Abbott, USA).

All the above mentioned preliminary tests were conducted at the respective institutes in Karachi. Out of 4000 female volunteer from the two universities, 144 otherwise healthy females tested positive for HBsAg. 2 out of the 144 HBsAg positive females were also found to be positive for anti-HCV antibodies. The other 28 positive HBV patients from Anklesaria Hospital were only tested for HBsAg and all 28 were positive for HBsAg. Hence, a total of 172 HBV positive samples (144 + 28 = 172) including the 39 HCV positive serum samples obtained from Karachi were used for genotypic evaluation at Claflin University, South Carolina, USA. Specific ethnicity was not determined but we assume these study participants represent a collection of different ethnic groups in Pakistan.

DNA/RNA extraction and amplification of 172 HBV positive samples: DNA was extracted for HBV, and RNA was extracted for HCV analysis from 200μL of all 172 positive HBV serum samples using PureLink™ Viral RNA/DNA Mini Kit according to manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen, CA). Amplification was carried out using puReTaq Ready –To-Go PCR Beads (Amersham Biosciences, UK).

Determination of HBV and HCV genotypes by nested PCR: The primer sets for first-round PCR and second-round PCR, PCR amplification protocol, and primers for both HBV and HCV genomes and genotyping amplification for all 172 samples followed previously reported methods [45, 46]. First round amplification targeted 1063bp for the HBV genome and 470bp for the HCV genome. These respective PCR products for both HBV and HCV were used as a template for genotyping different HBV genotypes A to F and HCV genotypes from 1 to 6. HBV A through HBV F genotypes and HCV 1 through 6 genotypes for each sample were determined by separating the genotype-specific DNA bands on 2% agarose gels, stained with ethidium bromide. The sizes of PCR products were estimated according to the migration pattern of a 50bp DNA ladder (Promega, WI).

Results:

Before screening for HBV status, all 4000 healthy female volunteers from the Department of Microbiology, University of Karachi, and the Department of Microbiology, Jinnah University for Women were subjected to routine physical checkups for exclusion criteria i.e., either they were apparently unhealthy or malnourished (23 volunteers were excluded). All 4000 serum samples were screened by immunochromatography for the presence of HBsAg, anti HBs antibodies and anti-HCV antibodies. Positive results were confirmed by ELISA. Out of 4000 subjects 144 (3.6%) tested positive for HB surface antigen (HBsAg), 2 (0.05%) were positive for anti-HCV antibodies, and 3856 (96.4%) were negative for HBsAg and 3998 (99.95%) were negative for HCV antibodies by both immunochromatography and ELISA. Out of these 144 individuals who tested positive for HBsAg, 20 (13.8%) were positive for anti-HB surface antibodies and 2 (1.4%) tested positive for anti-HCV antibodies. The rest of the 28 serum samples obtained from already diagnosed HBV positive samples from Anklesaria Hospital were only tested for HBsAg and were all positive for HBsAg.

The haematological parameters: WBC count, RBC count, hematocrit and platelet count of the 172 HBsAg positive individuals were within the normal recommended range of values, while mean Hb% was 9.8±1.6 g/dL. Direct bilirubin (0 to 0.3 mg/dL), indirect bilirubin (0.1 - 1.0 mg/dL), total serum bilirubin (0.3 to 1.9 mg/dL), ALT (0 - 36 U/L), AST (0 - 31 U/L) and alkaline phosphatase (20 - 125 U/L) were also within the normal range for 129 HBsAg positive individuals, except for the raised ALT (>36 U/L) and AST (>31 U/L) levels in 38 participants with a previous history of jaundice who were also positive for HBsAg.

All 172 samples that were positive for HBsAg were confirmed for the presence of different HBV genotypes as well as for different HCV genotypes by PCR to see the co-infection of both these viruses. Genotyping was carried out at the South Carolina Center for Biotechology, Department of Biology, Claflin University, Orangeburg, SC, U.S.A. For HBV: Mix A primers were targeted to amplify genotypes A, B and C, and primers for Mix B were targeted to amplify genotypes D, E and F. For HCV: primers for Mix A were targeted to amplify genotypes 1a, 1b, 1c, 3a, 3c and 4. Primers of Mix B for HCV were targeted to amplify genotypes 2a, 2b, 2c, 3b, 5a, and 6a.

Table 1. Prevalence of both single and co-infection of HBV genotypes among the apparently healthy female student sample and known HBV positive patients from Anklesaria hospital in Karachi.

| 2 Universities |

Samples |

Percentage |

| Total HBV |

144 |

|

| Genotype D |

70 |

48.6% |

| Genotype A |

8 |

5.5% |

| Genotype F |

7 |

4.9% |

| Genotype B |

5 |

3.5% |

| Genotype E |

3 |

2.1% |

| Genotype C |

2 |

1.4% |

| Co-infections of HBV Genotypes |

49/144 |

34% |

| Genotype B/D |

30/144 |

20.8% |

| Genotype A/D |

11/144 |

7.6% |

| Genotype A/D |

4/144 |

2.8% |

| Genotype B/C |

4/144 |

2.8% |

| Anklesaria Hospital |

Samples |

Percentage |

| Total HBV |

28 |

|

| Genotype D |

19 |

67.9% |

| Genotype A |

3 |

10.7% |

| Genotype B |

1 |

3.6% |

| Genotype C |

1 |

3.6% |

| Genotype F |

1 |

3.6% |

| Co-infections of HBV Genotypes |

|

|

| Genotype B/A |

3/28 |

10.7% |

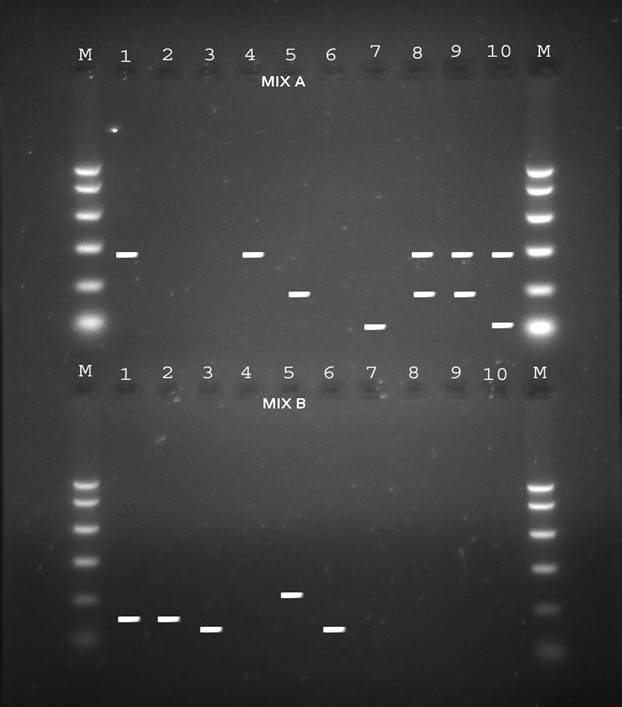

Figure 1: Electrophoresis patterns of PCR products from different HBV genotypes as determined by PCR genotyping system. Genotype A: 68bp, genotype B: 281bp, genotype C: 122bp, genotype D: 119bp, genotype E: 167bp and genotype F: 97bp.

Table 1 illustrates the prevalence of both single and co-infection of HBV genotypes from both the universities in Karachi and Anklesaria hospital. Representative 10 samples in Fig. 1 show single and co-infections for HBV.

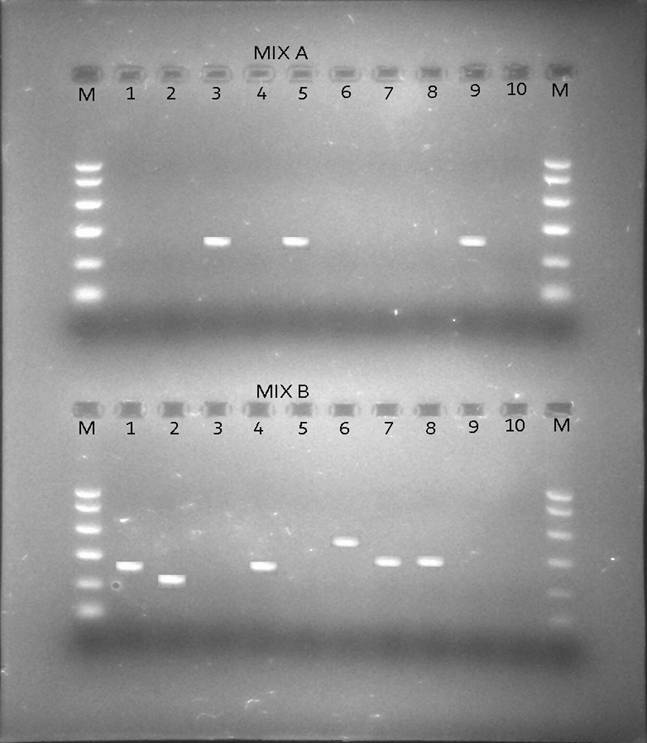

Besides looking at the HBV genotypic status of these 172 patients by PCR, we also looked at the HCV genotypic status of the positive HBV patients by PCR so as to see if there was existence of co-infection of the two viruses i.e. HBV and HCV in the same individuals as only 2 samples tested positive for anti-HCV antibodies by rapid immunochromatography. Table 2 shows the prevalence of HCV genotypes among the apparently healthy female student population from the 2 universities in Karachi and known HBV individuals samples obtained from Anklesaria hospital. Fig. 2 shows different HCV genotype infection in the 10 representative samples shown in Fig. 1 showing HBV infection with different genotypes.

Table 2. Prevalence of HCV genotypes among the apparently healthy female student sample, and known HBV individuals from Anklesaria hospital in Karachi.

| 2 Universities |

Samples |

Percentage |

| Total HCV/Total HBV |

39/144 |

27.1% |

| Genotype 3a |

26/39 |

66.6% |

| Genotype 6a |

5/39 |

12.8% |

| Genotype 3b |

4/39 |

10.3% |

| Genotype 5a |

4/39 |

10.3% |

| Anklesaria Hospital |

Samples |

Percentage |

| Total HCV/HBV |

4/28 |

14.3% |

| Genotype 3a |

2/28 |

7.14% |

| Genotype 2a |

1/28 |

3.6% |

| Genotype 5a |

1/28 |

3.6% |

Figure 2: The sizes of the genotype-specific bands for HCV amplified by PCR genotyping method are as follows: genotype 2a, 190 bp; genotype 3a, 258 bp; genotype 3b, 232 bp; genotype 5a, 417 bp; and genotype 6a, 300 bp.

To summarize the results it was found that out of 172 HBsAg positive samples from the two universities (144 HBV samples) and Anklesaria Hospital (28 HBV samples), 89 (51.7%) were genotype D, 11 were genotype A (6.4%), 8 were genotype F (4.6%), 6 were genotype B (3.5%), 3 were genotype E (1.7%), and 3 were genotype C (1.7%). Out of 43 positive for HCV by PCR from the two universities (39/144 HBV samples) and Anklesaria Hospital (4/28 HBV samples), 65.1% (28/43) showed infection with 3a, followed by genotypes 5a (5/43 = 11.6%), 6a (5/43 = 11.6%), 3b (4/43 = 9.3%) and 2a (1/43 = 2.3%).

Discussion:

Viral hepatitis due to HBV and HCV has significant morbidity and mortality worldwide. The global prevalence of HCV is 3% 38 and the carrier rate of HBsAg varies from 0.1% to 0.2% in Britain and the USA, to 3% in Greece and southern Italy and up to 15% in Africa and the Asia 39. Pakistan is highly endemic with HBV. Studies are too limited to give a clear picture of the prevalence of HBV at the national level, especially among apparently healthy individuals. Most previous studies targeted different small groups of individuals with some clinical indications, so they do not accurately reflect the overall prevalence in Pakistan40. Our previous study was conducted on a first group of 4000 healthy female students from the two universities i.e., Department of Microbiology, University of Karachi and Department of Microbiology, Jinnah University for Women for the prevalence of HBV. We have reported earlier that genotype D appears to be the dominant genotype prevalent in Karachi, Pakistan’s apparently healthy female population, and genotype B appears to be the next most prevalent genotype 41, 42. In this study we checked the prevalence of both HBV and HCV in a second group of 4000 healthy female students from the same two universities in Karachi mentioned above, as well as the already 28 diagnosed HBV patients from Anklesaria Hospital in Karachi, Pakistan.

Both HBV and HCV are present in the Pakistani population and there are varying reports of disease prevalence. HCV is one of the silent killer infections spreading undetected in Pakistan because there are often no clinical symptoms and, when HCV is diagnosed, considerable damage has already been done to the patient. In Pakistan alone, the prevalence of HBsAg has been reported to be from 0.99% to 10% in different groups of individuals 43 - 52 and 2.2% to 14% for HCV antibodies 53 - 56. A recent study conducted in Pakistan showed that out of 5707 young men tested, 95 (1.70%) were positive for anti-HCV and 167 (2.93%) for HBsAg 57. Our previous study showed the prevalence of HBsAg among young otherwise healthy women to be 4.5% 41,42. Our present study shows that the prevalence of HBsAg in otherwise young healthy women to be 3.6%, with 0.98% testing positive for anti-HCV antibodies. On the basis of other studies conducted in different provinces of Pakistan, we can say that there is a variation in the prevalence of HBsAg and HCV antibodies in the Pakistani population as the population sample selected is limited to a particular area or segment of the provinces.

HBV and HCV genotyping is important to track the route and pathogenesis of the virus. In particular, the variants may differ in their patterns of serologic reactivity, pathogenecity, virulence, and response to therapy. Both HBV and HCV has genetic variations which correspond to the geographic distribution and has been classified into 8 genotypes (A to H) on the basis of whole genome sequence diversity of greater than 8% and 6 genotypes (1 to 6) using restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of the 5’ non-coding region (NCR), respectively .

In this study genotyping was carried out for 6 HBV genotypes (A through F) and 6 HCV genotypes (1 through 6). This study suggests that the HBV D genotype is the most prevalent (114/144 = 79.2%) among otherwise healthy females alone or in co-infection with other HBV genotypes in Karachi, Sindh, Pakistan. In our previous study HBV D genotype was found to be ubiquitous (100%) among otherwise healthy females alone or in co-infection with other HBV genotypes in Karachi followed by genotype B 41,42. The earlier two studies conducted for prevalence of HBV genotypes in known hepatitis B positive patients in Pakistan report the prevalence of genotypes HBV A (68%) and HBV D (100%) in the province of Sindh 58,59. Interestingly, in this study we also found the HBV D genotype to be the prevalent genotype but it was followed by genotypes HBV A (5.5%) and HBV F (4.9%). The prevalence of genotype HBV B in this study was found to be 3.5% as our earlier study has shown the prevalence of genotype B in otherwise healthy females to be 16.1% 60. These findings respectively contradict and corroborate the previous studies for HBV genotype distributions reported here as the subjects in this study were also asymptomatic but comprised of second group of female volunteer students at the two universities. Out of 144 subjects positive for HBsAg, 10 reported a previous history of jaundice and the rest were not aware of their HBV status. In the nearby north Indian population, HBV D was reported as the predominant genotype (75%) in patients diagnosed with chronic liver disease (CLDB) 60. In this study we also found other HBV genotypes existed in the study population such as HBV genotype F (4.9%) followed by genotype E (2.1%), and genotype C (1.4%). We also saw mixed HBV infections of genotypes B and D, A and D, C and D as well as B and C (20.8%, 7.6%, 2.8% and 2.8%) among these otherwise healthy females.

Among the 28 diagnosed HBV patients from Anklesaria Hospital, 67.9% showed HBV genotype D infection followed by genotype A infection (10.7%). In this group of 28 HBV positive patients we also saw infections with genotypes B (3.6%), C (3.6%) and F (3.6%). This group exhibited 10.7% co-infection with genotypes B and A.

As far as the HCV status of these 144 otherwise healthy females who were HBV positive is concerned only 2 (1.4%) tested positive for HCV antibodies by rapid immunochromatography. But the PCR results showed 39 (27.15%) of these 144 otherwise healthy females that were HBV positive for different genotypes were also positive for HCV including the 2 otherwise healthy females that tested positive for HCV antibodies by rapid immunochromatography. Of the 39 HCV positive otherwise healthy females, we found the predominant HCV genotype to be 3a (66.6%) followed by genotypes 6a (12.8%), 3b (10.3%), and 5a (10.3%) infections. The earlier study conducted with samples from women at the two universities in Pakistan had shown that among the HCV positive apparently healthy females 51.44% were genotype 3a, 24.03% exhibited a mix of genotype 3a and 3b, 15.86% were genotype 3b, and 4.80% were genotype 1b 42. Interestingly, among the group of 28 diagnosed HBV patients, the prevalence of HCV 3a genotype infection was dominant but was 7.1% much lower than that found in the otherwise healthy females, followed by infections with genotypes 2a (3.6%) and 5a (3.6%). Hence we see there is 25% co-infection of both these viruses i.e., HBV and HCV among the HBsAg positive individuals. The sample of 28 HBV positive patients was from a hospital located in the center of the metropolis that represents an area of Karachi where sanitation, malnourishment, illiteracy, and lack of awareness is very common. Prostitution can also be considered as one factor in some of the localities of Karachi in the spread of both HBV and HCV.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, genotype D appears to be the dominant HBV genotype and genotype 3a for HCV appears to be prevalent in Sindh, Pakistan’s otherwise healthy young female population as well as in HBV diagnosed individuals. Co-infection of both the viruses i.e., HBV and HCV exists among HBsAg positive individuals. The young female participants were advised to seek appropriate medical care for both their own benefit and public health benefit.

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported from the grants: P2RR16461 (EXPORT): NIH, INBRE and EPS-044760: NSF EPSCoR.

Competing Interests

None declared

Author Details

SHAZIA TABASSUM HAKIM, SAMINA NOORALI, MEAGHEN ASHBY, OMAR BAGASRA: South Carolina Center for Biotechnology, Department of Biology, Claflin University, 400 Magnolia Street, Orangeburg, South Carolina 29115, U.S.A.

ANISAH BAGASRA, Department of History and sociology, Claflin University, 400 Magnolia Street, Orangeburg, South Carolina 29115, U.S.A.

SHAHANA U KAZMI, I.I.D.R.Lab., Department of Microbiology, University of Karachi, Karachi-75270, Pakistan

CORRESPONDENCE: Dr. Shazia Tabassum Hakim, Associate Professor & Chairperson, Virology & Tissue Culture Laboratory, Department of Microbiology, Jinnah University for Women, Nazimabad, Karachi-74600, Pakistan

Email: Shaz2971@yahoo.com |

References

- de Franchis R, Hadengue A, Lau G, Lavanchy D, Lok A, McIntyre N, Mele A, Paumgartner G, Pietrangelo A, Rodés J, Rosenberg W, Valla D; EASL Jury. EASL International Consensus Conference on Hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2003;39 Suppl 1:S3-25.

- WHO, Hepatitis B. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs204/en/index.html

- WHO, Hepatitis C. http://www.who.int/vaccine_research/diseases/hepatitis_c/en/

- Lauer GM, Walker BD. Hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2001 Jul 5;345(1):41-52.

- Okamoto H, Tsuda F, Sakugawa H, Sastrosoewignjo RI, Imai M, Miyakawa Y, Mayumi M. Typing hepatitis B virus by homology in nucleotide sequence: comparison of surface antigen subtypes. J Gen Virol. 1988; 69: 2575-2583.

- Norder H, Courouce AM, Magnius LO. Complete genomes, phylogenetic relatedness, and structural proteins of six strains of the hepatitis B virus, four of which represent two new genotypes. Virology. 1994; 198: 489-503.

- Stuyver L, De Gendt S, Van Geyt C, Zoulim F, Fried M, Schinazi RF, Rossau, R. A new genotype of hepatitis B virus: complete genome and phylogenetic relatedness. J Gen Virol. 2000; 81: 67-74.

- Arauz-Ruiz P, Norder H, Robertson BH, Magnius LO. Genotype H: a new Amerindian genotype of hepatitis B virus revealed in Central America. J Gen Virol. 2002; 83: 2059-2073.

- Simmonds, P., E. C. Holmes, T. A. Cha, S. W. Chan, F. McOmish, B. Irvine, E. Beall, P. L. Yap, J. Kolberg, and M. S. Urdea. Classification of hepatitis C-virus into six major genotypes and a series of subtypes by phylogenetic analysis of the NS5 region. J. Gen. Virol. 1993;74:2391–2399.

- Cha, T. A., E. Beall, B. Irvine, J. Kolberg, D. Chein, G. Ruo, and M. S. Urdea. At least five related but distinct hepatitis C viral genotypes exist. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1992; 89:7144–7148.

- Murphy, D., B. Willens, and G. Delage. Use of the non-coding region for the genotyping of hepatitis C-virus. J. Infect. Dis. 169:473–474. Miyakawa Y, Mizokami M (2003) Classifying hepatitis B virus genotypes. Intervirology. 1994; 46: 329-338.

- Liu CJ, Kao JH, Chen PJ, Lai MY, Chen DS. Molecular epidemiology of hepatitis B viral serotypes and genotypes in Taiwan. J Biomed Sci. 2002; 9: 166-170.

- Kao JH, Chen PJ, Lai MY, Chen DS. Hepatitis B genotypes correlate with clinical outcomes in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2000; 118: 554-559.

- Kao JH, Chen PJ, Lai MY, Chen DS. Clinical and virological aspects of blood donors infected with hepatitis B virus genotypes B and C. J Clin Microbiol. 2002; 40: 22-25.

- Bae SH, Yoon SK, Jang JW, Kim CW, Nam SW, Choi JY, Kim BS, Park YM, Suzuki S, Sugauchi F,Mizokami M. Hepatitis B virus genotype C prevails among chronic carriers of the virus in Korea. J Korean Med Sci . 2005;20: 816-820.

- Ferreira RC, Teles SA, Dias MA, Tavares VR, Silva SA, Gomes SA, Yoshida CF, Martins RM. Hepatitis B virus infection profile in hemodialysis patients in Central Brazil: prevalence, risk factors, and genotypes. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2006; 101: 689-692.

- Kar P, Polipalli SK, Chattopadhyay S, Hussain Z, Malik A, Husain SA, Medhi S, Begum N. Prevalence of hepatitis B virus genotype D in Precore Mutanrs among chronic liver disease patients from New Delhi, India. Dig Dis Sci. 2007; 52: 565-569.

- Alavian SM, Keyvani H, Rezai M, Ashayeri N, Sadeghi HM. Preliminary report of hepatitis B virus genotype prevalence in Iran. World J Gastroenterol. 2006; 12: 5211-5213.

- Abbas Z, Muzaffar R, Siddiqui A, Naqvi SA, Rizvi SA. Genetic variability in the precore and core promoter regions of hepatitis B virus strains in Karachi. BMC Gastroenterol . 2006;6: 20.

- Amini-Bavil-Olyaee S, Alavian SM, Adeli A, Sarrami-Forooshani R, Sabahi F, Sabouri E, Tavanga, HR, Azizi M, Mahboudi F. Hepatitis B virus genotyping, core promoter, and precore/core mutations among Afghan patients with hepatitis B: a preliminary report. J Med Virol. 2006; 78: 358-364.

- Huy TT, Ishikawa K, Ampofo W, Izumi T, Nakajima A, Ansah J, Tetteh JO, Nii-Trebi N, Aidoo S, Ofori-Adjei D, Sata T, Ushijima H, Abe K. Characteristics of hepatitis B virus in Ghana: full length genome sequences indicate the endemicity of genotype E in West Africa. J Med Virol. 2006; 78: 178-184.

- Olinger CM, Venard V, Njayou M, Oyefolu AO, Maiga I, Kemp AJ, Omilabu S.A., le Faou A, Muller CP. Phylogenetic analysis of the precore/core gene of hepatitis B virus genotypes E and A in West Africa: new subtypes, mixed infections and recombinations. J Gen Virol. 2006; 87: 1163-1173.

- 23.Campos RH, Mbayed VA, Pineiro Y, Leone FG. Molecular epidemiology of hepatitis B virus in Latin America. J Clin Virol. 2005; 34: S8-S13.

- Parana R, Almeida D. HBV epidemiology in Latin America. J Clin Virol . 2005;34: S130-S133.

- 25.Stuyver L, De Gendt S, Van Geyt C, Zoulim F, Fried M, Schinazi RF, Rossau, R. A new genotype of hepatitis B virus: complete genome and phylogenetic relatedness. J Gen Virol. 2000; 81: 67-74.

- 26.Sanchez LV, Tanaka Y, Maldonado M, Mizokami M, Panduro A. Difference of hepatitis B genotype distribution in two groups of Mexican patients with different risk factors. High prevalence of genotype H and G. Intervirology. 2007; 50: 9-15.

- 27.Arauz-Ruiz P, Norder H, Robertson BH, Magnius LO. Genotype H: a new Amerindian genotype of hepatitis B virus revealed in Central America. J Gen Virol . 2002;83: 2059-2073.

- Larke, B., Y. W. Hu, M. Krajden, V. Scalia, S. K. Byrne, L. R. Boychuk, and J. Klein. Acute nosocomial HCV infection detected by NAT of a regular blood donor. Transfusion. 2002; 42:759–765.

- Larsen C, Pialoux G, Salmon D, Antona D, Le Strat Y, Piroth L, Pol S, Rosenthal E, Neau D, Semaille C, Delarocque Astagneau E. Prevalence of hepatitis C and hepatitis B infection in the HIV-infected population of France, 2004. Euro Surveill. 2008;13(22). pii: 18888.

- Lee HC, Ko NY, Lee NY, Chang CM, Ko WC. Seroprevalence of viral hepatitis and sexually transmitted disease among adults with recently diagnosed HIV infection in Southern Taiwan, 2000-2005: upsurge in hepatitis C virus infections among injection drug users. J Formos Med Assoc. 2008;107(5):404-11.

- Jain M, Chakravarti A, Verma V, Bhalla P. Seroprevalence of hepatitis viruses in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2009;52(1):17-9.

- Nagu TJ, Bakari M, Matee M. Hepatitis A, B and C viral co-infections among HIV-infected adults presenting for care and treatment at Muhimbili National Hospital in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:416.

- Kim JH, Psevdos G, Suh J, Sharp VL. Co-infection of hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients in New York City, United States. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14(43):6689-93.

- Anna Gyarmathy V, Neaigus A, Ujhelyi E. Vulnerability to drug-related infections and co-infections among injecting drug users in Budapest, Hungary. Eur J Public Health. 2009.

- Yun H, Kim D, Kim S, Kang S, Jeong S, Cheon Y, Joe K, Gwon DH, Cho SN, Jee Y. High prevalence of HBV and HCV infection among intravenous drug users in Korea. J Med Virol. 2008;80(9):1570-5.

- Yildirim B, Barut S, Bulut Y, Yenışehırlı G, Ozdemır M, Cetın I, Etıkan I, Akbaş A, Atiş O, Ozyurt H, Sahın S. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B and C viruses in the province of Tokat in the Black Sea region of Turkey: A population-based study. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2009 ;20(1):27-30.

- Demirtürk N, Demirdal T, Toprak D, Altindiş M, Aktepe OC. Hepatitis B and C virus in West-Central Turkey: seroprevalence in healthy individuals admitted to a university hospital for routine health checks. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2006;17(4):267-72.

- Bonkovsky HL, Mehta S. Hepatitis C: a review and update. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 2001; 44:159–79.

- Sherlock S, Dooley J, eds. Diseases of the liver and biliary system. London, Blackwell Science, 2002:290–316.

- Malik IA, Legters LJ, Luqman M, Ahmed A, Qamar MA, Akhtar KA, Quraishi MS, Duncan F, Redfield RR. The serological markers of hepatitis A and B in healthy population in Northern Pakistan. J Pak Med Assos. 1988; 38: 69–72.

- Noorali S, Hakim ST, McLean D, Kazmi SU, Bagasra O. Prevalence of Hepatitis B virus genotype D in females in Karachi, Pakistan. J Infect Developing Countries. 2008; 2:373-378.

- Hakim ST, Kazmi SU, Bagasra O. Seroprevalence of Hepatitis B and C Genotypes Among Young Apparently Healthy Females of Karachi-Pakistan. Libyan J Med. 2008; 3: 66-70.

- Ahmed M, Tariq WUZ. Extent of past hepatitis B virus exposure in asymptomatic Pakistani young recruits. Pak J Gasteroenterol. 1991; 5: 7–9.

- Rehman K, Khan AA, Haider Z, Shahzad A, Iqbal J, Khan RU, Ahmad S, Siddiqui A, Syed SH. Prevalence of seromarkers of HBV and HCV in health care personnel and apparently healthy blood donors. J Pak Med Assoc.1996; 46: 152–154.

- Zuberi SJ, Samad F, Lodi TZ, Ibrahim K, Maqsood R. Hepatitis and hepatitis B surface antigen in health-care personnel. J Pak Med Assoc. 1997; 27: 373-375.

- Yousuf M, Hasan SMA, Kazmi SH. Prevalence of HbsAg among volunteer blood donors in Bahawalpur division. The Professional. 1998; 5: 267-271.

- Qasmi SA, Aqeel S, Ahmed M, Alam SI, Ahmad. A. Detection of Hepatitis B virus in normal individuals of Karachi. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2000; 10: 467–469.

- Zakaria M, Ali S, Tariq GR, Nadeem M.Prevalence of anti-hepatitis C antibodies and hepatitis B surface antigen in healthy male naval recruits. Pak Armed Forces Med J. 2003; 53: 3–5.

- Farooq MA, Iqbal MA, Tariq WUZ, Hussain AB, Ghani I. Prevalence of hepatitis B and C in healthy cohort. Pak J Pathol. 2005; 16: 42–46.

- Abbas Z, Shazi L, Jafri W. Prevalence of hepatitis B in individuals screened during a countrywide campaign in Pakistan. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2006; 16: 497-498.

- Masood Z, Jawaid M, Khan RA, Rehman SU. Screening for hepatitis B and C: a routine preoperative investigation? Pak J Med Sci. 2005; 21: 455–459.

- Bhopal FG, Yousaf A, Taj MN. Frequency of hepatitis B and C: surgical patients in Rawalpindi general hospital. Prof Med J. 1999; 6: 502-509.

- Zuberi SJ. An overview of HBV/HCV in Pakistan. Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association. 1998; 37:S12–8.

- Mujeeb SA, Aamir K, Mehmood K. Seroprevalence of HBV, HCV and HIV infections among college going first time voluntary blood donors. Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association. 2000; 50:269–70.

- Asif N, Khokar N, Ilahi F. Seroprevalence of HBV, HCV and HIV infection among voluntary non-remunerated and replace-ment donors in Northern Pakistan. Paki-stan journal of medical sciences. 2004; 20:24–8.

- Khokar N, Gill ML, Malik GJ. General seroprevalence of hepatitis C and hepatitis B virus infections in population. Journal of the College of Physicians and Surgeons Pakistan. 2004; 14(9):534–36.

- T. Butt and M.S. Ami. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B and C infections among young adult males in Pakistan. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. 2008; 14(4): 791-797.

- Idrees M, Khan S, Riazuddin S. Common genotypes of hepatitis B virus. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2004; 14: 344-347.

- Abbas Z, Muzaffar R, Siddiqui A, Naqvi SA, Rizvi SA. Genetic variability in the precore and core promoter regions of hepatitis B virus strains in Karachi. BMC Gastroenterol . 2006; 6: 20.

- Chattopadhyay S, das BC, Kar P. Hepatitis B virus genotypes in chronic liver disease patients from New Delhi, India. World J Gastroenterol. 2006; 12: 6702-6706.

The above article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.