Abrar Hussain and Mariwan Husni

Abstract

The Clinical Assessment of Skills and Competencies (CASC) is the final examination towards obtaining the Membership of the Royal College of Psychiatrists (MRCPsych). It assesses skills in history taking, mental state examination, risk assessment, cognitive examination, physical examination, case discussion and difficult communication.1 The CASC is the only clinical examination, having replaced the earlier format, which had clinical components at two stages.

|

Background

The Royal College of Psychiatrists first introduced the CASC in June 2008. It is based on the OSCE style of examination but is a novel method of assessment as it tests complex psychiatric skills in a series of observed interactions.2 OSCE (Observed Structured Clinical Examination) is a format of examination where candidates rotate through a series of stations, each station being marked by a different examiner. Before the CASC was introduced, candidates appeared for OSCE in Part 1 and the ‘Long Case’ in Part 2 of the MRCPsych examinations. The purpose of introducing of the CASC was to merge the two assessments.3

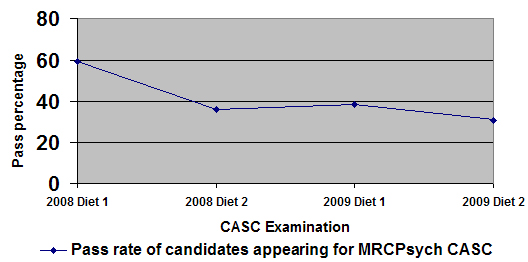

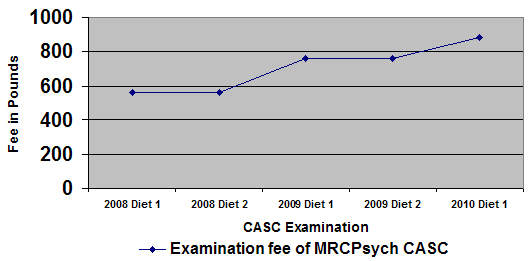

The first CASC diet tested skills in 12 stations in one circuit. Subsequently, 16 stations have been used in two circuits - one comprising eight ‘single’ and the other containing four pairs of ‘linked’ scenarios. Feedback is provided to unsuccessful candidates in the form of ‘Areas of Concern’.4 The pass rate has dropped from almost 60% in the first edition to around 30% in the most recent examination (figure 1). Reasons for this are not known. The cost of organising the examination has increased and candidates will be paying £885 to sit the examination in 2010 in the United Kingdom (figure 2).

Figure 1

We are sharing our experience of the CASC examination and we hope that it will be useful reading for trainees intending to appear for the CASC and for supervisors who are assisting trainees in preparation. In preparing this submission, we have also made use of some anecdotal observations of colleagues. We have also drawn from our experience in organising local MRCPsych CASC training and small group teaching employing video recording of interviews.

Figure 2

CASC is an evaluation of two domains of a psychiatric interview: ‘Content’ (the knowledge for what you need to do) and ‘Process’ (how you do it). The written Papers (1, 2 and 3) test the knowledge of candidates. We therefore feel that the candidates possess the essentials of the ‘Content’ domain. Therefore, the more difficult aspect is demonstrating an appropriate interview style to the examiner in the form of the ‘Process’.

This article discusses the preparation required before the examination followed by useful tips on the day of the examination.

Before the examination day (table 1)

|

Table 1: Tips before the examination day

|

|

Factor

|

Technique

|

|

- The mindset

|

- Have a positive attitude

|

|

- Time required

|

- Start preparing early

|

|

- Analysing areas for improvement

|

- Use ‘Areas of Concern’

|

|

- Practice

|

- Group setting and individual sessions

- Feedback from colleagues using video

|

The mindset

In our view, preparation for the CASC needs to begin even before the application form is submitted. Having a positive mindset will go a long way in enhancing the chances of success.5 It is therefore a must to believe in ones ability and dispel any negative cognition. Understandably, previous failure in the CASC can affect ones confidence, but a rational way forward would be to consider the failure as a means of experiential learning, a very valuable tool. Experiential learning for a particular person occurs when changes in judgments, feelings, knowledge or skills result from living through an event or events.6

Time required

Starting to prepare early is crucial as it gives time to analyse and make the required changes to the style of the interview. For instance, a good interview requires candidates to use an appropriate mixture of open and closed questions. Candidates who have been following this technique in daily practice will find it easier to replicate this in examination conditions when there is pressure to perform in limited time. However, candidates who need to incorporate this into their style will need time to change their method of interview.

Analysing areas for improvement

Candidates need to identify specific areas where work is needed to improve their interview technique. The best way to accomplish this is by an early analysis of their interview technique by a senior colleague, preferably a consultant who has examined candidates in the real CASC examination. We think its best to provide feedback using the Royal College’s ‘Areas of Concern’ - individual parameters used to provide structured feedback in the CASC. This will help to accustom oneself with the expectation in the actual examination.

Requesting more than one ‘examiner’ to provide feedback is useful as it can provide insight into ‘recurring mistakes’ which may have become habit. In addition, different examiners might provide feedback on various aspects of the interview style. The Calgary-Cambridge guide7, 8 is a collection of more than 70 evidence-based communication process skills and is a vital guide to learn the basics of good communication skills.

Practice

We believe that it is important to practice in a group setting. Group work increases productivity and satisfaction.9 The aim of group practice is to interact with different peers which will help candidates to become accustomed to varying communication styles. Group practice is more productive when the group is dynamic so that novelty prevails. Practising with the same colleagues over a period of weeks carries the risk of perceiving a false sense of security. We feel this is because candidates get used to the style of other candidates and, after a period of time, may not recognise areas for improvement.

Another risk of a static group is candidates may not readily volunteer areas for improvement - either because they may feel they are offending the person or, more importantly, because the same point may have been discussed multiple times before! Whenever possible, an experienced ‘examiner’ may be asked to facilitate and provide feedback along the lines of ‘Areas of Concern’. However candidates need to be conscious of the pitfalls of group work and negative aspects such as poor decisions and conflicting information.

In addition to group practice, candidates would benefit immensely from individual sessions where consultants and senior trainees could observe their interview technique. Candidates could interview patients or colleagues willing to role-play. We have observed that professionals from other disciplines like nurses and social workers are often willing to help in this regard. Compared to group practice, this needs more effort and commitment to organise. Consultants, with their wealth of experience, would be able to suggest positive changes and even subtle shifts in communication styles which may be enough to make a difference. We found that video recording the sessions, and providing feedback using the video clips, helps candidates to identify errors and observe any progress made.

The feedback of trainees who appeared in the CASC examination included that attending CASC revision courses had helped them to prepare for the examination. It is beyond the remit of this article to discuss in detail about individual courses. The majority of courses employ actors to perform role-play and this experience is helpful in preparing for the CASC. Courses are variable in style, duration and cost. Candidates attending courses early in their preparation seem to benefit more as they have sufficient time to apply what they have learnt.

During the examination (table 2)

|

Table 2: Tips during the examination

|

|

Factor

|

Technique

|

|

- Reading the task

|

- Fast and effective reading

- Focus on all sub-tasks

|

|

- Time management

|

- ‘Wrap up’ in the final minute

|

|

- The golden minute

|

- Establish initial rapport

|

|

- Leaving the station

|

- Avoid ruminating on previous station

|

|

- Expecting a surprise

|

- Fluent conversation with empathy

|

Reading the task

Inadequate reading and/or understanding of the task leads to poor performance. Candidates have one minute preparation time in single stations and two minutes in linked stations. We have heard from many candidates who appeared in the examination that some tasks can have a long history of the patient. This requires fast and effective reading by using methods such as identifying words without focusing on each letter, not sounding out all words, skimming some parts of the passage and avoiding sub-vocalisation. It goes without stating that this needs practice.

CASC differs from the previous Part 1 OSCE exam in that it can test a skill in more depth. For example it may ask to demonstrate a test for focal deficit in cognition that may not be detected by conducting a superficial mini mental state examination.

Candidates need to ensure they understand what is expected of them before beginning the interview. In some stations, there are two or three sub-tasks. We believe that all parts of a task have a bearing on the marking.

An additional copy of the ‘Instruction to Candidate’ will be available within the cubicles. We suggest that when in doubt, candidates should refer to the task so that they don’t go off track. Referring to the task in a station will not attract negative marking but it is best done before initiating the interview.

Time management

It is crucial to manage time within the stations. A warning bell rings when one minute is left for the station to conclude. This can be used as a reference point to ‘wrap up’ the session. If the station is not smoothly concluded before the end of the final bell candidates may come across as unprofessional. Candidates also run the risk of losing valuable time to read the task for the next station.

Single stations last for seven minutes and linked stations last for ten minutes. Candidates who have practiced using strict timing are able to sense when the warning bell will ring. They are also able to use the final minute to close the session appropriately.

Having stressed the importance of finishing the stations on time, it is also vital to understand that an early finish can lead to an uncomfortable silence in the station. This may give the examiner the impression that the candidate did not cover the task. We feel that there will always be something more the candidate could have explored!

The awkward silence in the above scenario can potentially make the candidate feel anxious and ruminate on the station which must be avoided.

The golden minute

First impressions go a long way in any evaluation and the CASC is no different in this regard.10 Candidates need to open the interview in a confident and professional manner to be able to make a lasting impact and establish a better rapport. Observing peers, seniors and consultants interacting with patients is a good learning experience for candidates in this regard.

Candidates who do well are able to demonstrate their ability to gain the trust of the actors in this crucial passage of the interaction. Basic aspects such as a warm and polite greeting, making good eye contact, and clear introduction and explanation of the session will go a long way in establishing initial rapport which can be strengthened as the interview proceeds.

The first minute in a station is important as it sets the tone of the entire interaction. A confident start would certainly aid candidates in calming their nerves. Actors are also put at ease when they observe a doctor who looks and behaves in a calm and composed manner.

Leaving the station behind

Stations are individually marked in the CASC. Performance in one station has no bearing on the marking process in the following stations. It is therefore important not to ruminate about previous stations as this could have a detrimental effect on the performance in subsequent stations. The variety of tasks and scenarios in the CASC means that candidates need to remain fresh and alert. Individual perceptions of not having performed well in a particular station could be misleading as the examiner may have thought otherwise. Candidates need to remember that they will still be able to pass the examination even if they do not pass all stations.

Expecting a sorprise

Being mentally prepared to expect a new station is good to keep in mind while preparing and also on the day of the examination. Even if candidates are faced with a ‘surprise station’, it is unlikely that the station is completely unfamiliar to them. It is most likely that they have encountered a similar scenario in real life. Maintaining a calm and composed demeanour, coupled with a fluent conversation focused on empathy and rapport, will be the supporting tools to deal with a station of this kind.

Conclusion

The CASC is a new examination in psychiatry. It tests a range of complex skills and requires determined preparation and practice. A combination of good communication skills, time management and confident performance are the key tools to achieve success. We hope that the simple techniques mentioned in this paper will be useful in preparing for this important examination. Despite the falling pass rate, success in this format depends on a combination of practice and performance and is certainly achievable.

Competing Interests

Abrar Hussain is actively involved in organising the local CASC revision and MRCPsych course in Northwest London. Mariwan Husni is actively involved in organising the local CASC revision and MRCPsych course in Northwest London. He is also a CASC examiner for The Royal College of Psychiatrists.

Author Details

ABRAR HUSSAIN MBBS MRCPsych, Specialty Registrar in General Adult Psychiatry, Harrow Assertive Outreach Team, Bentley House, 15-21 Headstone Drive, Harrow, Middlesex, HA3 5QX

MARIWAN HUSNI FRCPC FRCPsych Consultant Psychiatrist in General Adult Psychiatry Northwick Park Hospital Watford Road Harrow, HA1 3UJ

CORRESPONDENCE: Dr Abrar Hussain MBBS MRCPsych, Specialty Registrar in General Adult Psychiatry, Harrow Assertive Outreach Team, Bentley House, 15-21 Headstone Drive, Harrow, Middlesex, HA3 5QX

Email: abrar71@yahoo.com |

References

1. Royal College of Psychiatrists. MRCPsych CASC Blueprint. Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2009 (http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/pdf/MRCPsych%20CASC%20Blueprint%202.pdf)

2. Royal College of Psychiatrists. CASC Candidate guide. Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2009 (http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/pdf/CASC%20Guide%20for%20Candidates%20UPDATED%20Feb%202009.pdf)

3. Thompson C M. “Will the CASC stand the test? A review and critical evaluation of the new MRCPsych clinical examination.” The Psychiatrist (2009) 33: 145-148

4. Royal College of Psychiatrists. Clinical Assessment of Skills and Competence- Areas of Concern. Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2009 (http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/pdf/CASC%20-%20Areas%20of%20Concern.pdf)

5. Lyubomirsky S, King L, Deiner E. “The Benefits of Frequent Positive Affect: Does Happiness Lead to Success?” Psychological Bulletin (2005) 131 (6): 803–855

6. Itin C M. “Reasserting the Philosophy of Experiential Education as a Vehicle for Change in the 21st Century.” The Journal of Experiential Education(1999) 22 (2): 91-98

7. Kurtz S M, Silverman J D, Draper J. Teaching and Learning Communication Skills in Medicine. Radcliffe Medical Press (Oxford) (1998)

8. Silverman J D, Kurtz S M, Draper J. Skills for Communicating with Patients. Radcliffe Medical Press (Oxford) (1998)

9. Campion M A, Medsker G J, Higgs A C. “Relations between work group characteristics and effectiveness: Implications for designing effective work groups.” Personnel Psychology (1993) 46: 823-850

10. Nisbett R E, Wilson T D. "The halo effect: Evidence for unconscious alteration of judgments." Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (1977) 35 (4): 250-256

The above article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.