Adaptation Practice: Teaching doctors how to cope with stress, anxiety and depression by developing resilience

Clive Sherlock & Chris John

Cite this article as: BJMP 2016;9(2):a916

|

|

Abstract Aims Doctors suffer from stress, anxiety and depression more than the general population. They tell patients to seek help but are reluctant to themselves. Help for them is at best inadequate. This is a preliminary study to see if a radically different approach could change this. We offered a six-month training course of Adaptation Practice (The Practice), a behavioural programme of self-discipline designed to deal with stress, anxiety and depression, to see if it would be acceptable and effective for a group of General Practitioners (GPs). Methods All GPs in one UK Health Area were asked if they would be interested in a course to cope with stress, anxiety and depression. Respondents completed the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) and those with scores ≥ 8 were invited to the course. Scores for those who attended were compared with scores for a control group. The study group wrote anonymous self-assessments. Results Of 314 registered GPs, 225 responded. 152 were openly interested in the course. Of these, 71 had HADS scores ≥ 8 for anxiety, 35 for depression and 79 for both; 29 applied to attend the course. Due to prior commitments 14 could not attend and 15 did attend. All 15 found Adaptation Practice acceptable. Their HADS scores improved significantly compared with those of the control group and their self-assessments were positive. Conclusions Doctors tend to be secretive about their own difficulties coping with emotional and psychological problems and are reluctant to admit a need for personal help. However, 68% of respondents were willing to express an open interest in learning how to cope. This in itself was a breakthrough. We suggest that this was because the course was offered as postgraduate training with no suggestion of illness, treatment or stigma. All those learning Adaptation Practice found it acceptable and recognised significant positive changes in themselves, which were supported by significant positive changes in the HADS scores and the authors’ clinical assessments. Keywords: doctors, general practitioner, GP, stigma, treatment, disclosure, cope, stress, anxiety, depression, mental illness, adaptation practice, educationAbbreviations: GP – General medical practitioner, HADS – Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, SSS – Simple Stress Scale, LSD – Fisher’s Least Significant Difference, SPSS – Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, AP – Adaptation Practice |

INTRODUCTION

Like doctors in other specialties, general medical practitioners (GPs) are exposed daily to human suffering which most of society try to avoid.1 The World Health Organisation (WHO) predicts that by 2030 depression will be ‘the leading cause of disease burden globally.’ And that 1 in 4 individuals seeking health care are ‘troubled by mental or behavioural disorders, not often correctly diagnosed and/or treated.’2, 3 Doctors suffer from stress, anxiety and depression (as well as vascular disease, cirrhosis of the liver and road traffic accidents) more than the general population.4-10 Help for doctors is inadequate and doctors are reluctant to seek help.1, 4, 11 Where improvement is suggested, it is usually as counselling and general support.11 Instead of ‘more of the same’, we suggest a radically different approach: Adaptation Practice, which Clive Sherlock pioneered and has taught since 1975. It is pragmatic and safe. This study tests its acceptability to a group of working doctors.

Doctors bear the responsibility for fellow human beings’ health, well-being and, often, for their very survival. Added to this, GPs are under increasing pressure from more patients who want more cures and from health service managers who demand clinical excellence and more administration and more managerial skills of them. GPs’ stress is related to increasing workloads, changes to meet requirements of external bodies, insufficient time to do the job justice, paperwork, long hours, dealing with problem patients, budget restraints, eroding of clinical autonomy, and interpersonal problems.6, 10, 12 The recent rise in the GMC’s Fitness to Practice complaints related to patients’ expectations of doctors is yet another stress making them feel threatened.13

Job satisfaction for GPs is at its lowest level since a major survey started ten years ago, while levels of stress are at their highest. In 2015 there had been a year on year increase in the number of GPs reporting a slight to strong likelihood of their leaving ‘direct patient care’ within five years, with 53% of those under 50 and 87% of those over 50.6

By nature and vocation, GPs want to help but too much pressure is unbearable and takes its toll. They work, not with numbers, data or profits, but with human suffering, which, inevitably, is an emotional burden because of compassion and because it makes them aware of their own vulnerabilities and mortality. 3, 14 When combined with heavy workloads and low morale, doctors themselves inevitably suffer emotionally and psychologically.7, 10, 14 At the same time they and others feel they should be invincible.1, 15-17 What professional help is available for them is inadequate.3, 4, 18, 19 Existing support services in the UK are underfunded and sporadic.4 Some are outsourced to counselling services, and some of these are by telephone. Doctors do not like to be counselled and are reluctant to use these services.4, 15, 17

Doctors themselves are the mainstay for diagnosis and treatment of mental illnesses but are not adequately trained.3, 20 Mental illness is not well understood and conventional treatments are insufficient and often harmful. 15, 20-23 Consequently, doctors do not have the wherewithal to deal with the emotional and psychological problems they face every day in their patients and often in themselves, their colleagues and their families.4, 12, 18

There is significant prejudice, stigmatisation and intolerance of mental ill health within the medical profession due to lack of understanding and fear.3, 4, 9, 15, 17, 20, 21, 22, 24 This not only affects how doctors treat their patients, it also exacerbates their own difficulties when they suffer with emotional and psychological problems themselves, and dissuades them from self-disclosure and from seeking professional help.3, 4, 8, 10, 18, 20, 25, 26 To succumb to stress, anxiety and depression is seen as being weak and inadequate as a person and in particular as a doctor. 3, 4, 15 Doctors think they should know the answers and should be able to cope.1, 4

However, doctors are willing to learn work-related skills as this present study set out to show.11 Adaptation Practice is training; not treatment or therapy. The course in this study was presented as a postgraduate programme for doctors to learn how to cope with stress, anxiety and depression.

METHOD

Recruitment

We asked by letter all 314 GPs registered in one UK urban and semi-rural Health Authority Area if they would be interested in a course of twelve fortnightly seminars to learn the basics of Adaptation Practice: a programme of self-discipline to cope with stress, anxiety and depression. Included, was the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). Those who responded and whose HADS scores were ≥ 8 (the threshold for anxiety and depression) were invited to the course.

Stress, anxiety and depression

Anxiety and depression were assessed by the HADS and stress by a simple stress scale (SSS – see Table 1) one month before training started, immediately prior to training, at three months (mid-way through the training) and at six months (at the end of training).

| Table 1: The Simple Stress Scaledeveloped by Clive Sherlock and used to assess the level of stress in a subject. A total score ≥ 8, out of a maximum of 24 is suggestive of a disturbing level of stress or burnout.

I feel I am under too much stress: I feel exhausted: I care about other people: I have lost my appetite: I sleep well: I am irritable: I feel dissatisfied: I feel run down: |

Evaluation of Adaptation Practice

Half of those GPs who applied for the course were unable to attend because of prior commitments on the days planned for the course. These acted as a control group. Those who attended the course were the study group. All those who attended were also assessed in private by the authors immediately before and throughout the course. At the end of the course the doctors wrote anonymous self-assessments.

Training in Adaptation Practice

Those attending the course were taught not to express and suppress upsetting and disturbing emotion, not to distract their attention from it (including not to think about it and not to analyse it) and not to numb themselves to it with chemicals (alcohol, recreational drugs or prescribed medication). Instead, they learned how to engage with their moods and feelings physically, not cognitively, and how not to engage with thoughts about them. They were instructed to practise this six days a week with whatever they were doing, wherever they were. They were all offered unrestricted confidential telephone and e-mail support from the authors between training sessions and after the course had finished.

Statistical Analyses

The results are reported as means ± standard errors of the means. The scores were normally distributed and the data were analysed by analysis of variance with additional paired comparisons within periods, using the LSD method. Correlations were determined using Pearson’s correlation. The analyses were carried out using the statistical software programme SPSS 17.0 for Windows.

RESULTS

Recruitment

Of 314 registered GPs, 225 (72%) responded to our initial contact, and of these 152 (68%) said they would be interested in participating in the training course. Recruitment was restricted to those with HADS scores ≥ 8. Of the 225 who responded there were 71 (32%) for anxiety, 35 (16%) for depression, and 79 (35%) for both. 29 (13%) applied to attend the course. All were experienced GPs. 15 of these attended and 14 were not able to attend because of pre-existing commitments on the course dates. They asked for alternative dates but these were not available.

At the initial assessment (one month before the course started) there were significant correlations between the scores for anxiety and depression (P < 0.001), anxiety and stress (P < 0.001) and depression and stress (P < 0.001). At the second assessment immediately before the course started these correlations remained highly significant.

Effects of Adaptation Practice

All those who attended the course reported a subjective improvement in their abilities to cope with their own stress, anxiety and depression, and in their sense of well-being.

Anxiety

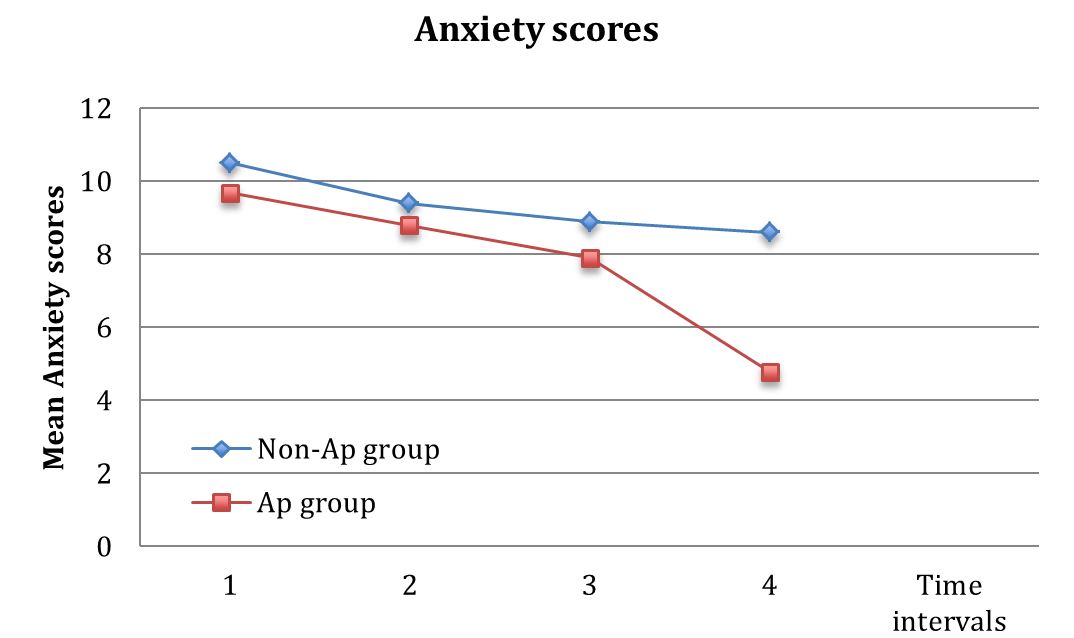

There were no significant differences between the control and study groups either one month before the start (P=0.949) or immediately before the first session (P=0.914). The anxiety scores in both groups remained greater than 8 at both assessments (Figure 1). At the mid-point of the course the mean score had fallen slightly in the study group (Figure 1) but the difference was not significant (P=0.652) By the end of the course the mean anxiety score in the study group was significantly lower (P=0.008) than that of the control group (Figure 1). The mean scores for anxiety decreased over the 4 assessments. This tendency was significant in the study group (P=0.002) but not in the control group (P=0.567).

Figure 1: The mean anxiety scores and standard errors of the means (SEM) for a control group and a study group of doctors with pre-existing signs of anxiety, assessed twice before, once during and once at the end of a six-month course in Adaptation Practice.

Depression

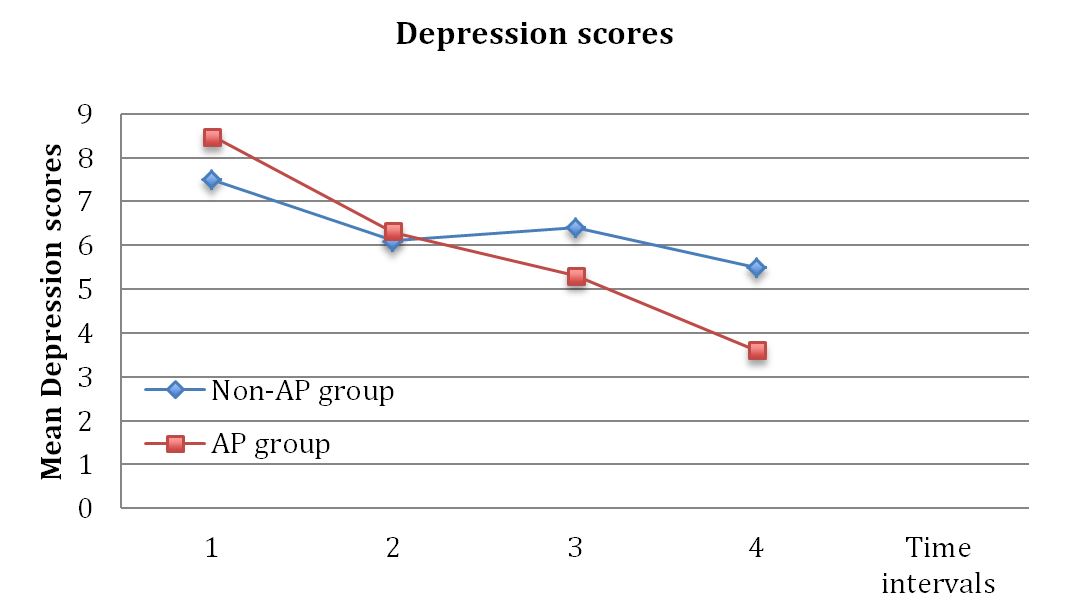

There were no significant differences between the control and the study groups either one month before the start (P=0.310) or immediately before the first session (P=0.880). The mean HADS scores for depression before training were all greater than 8 (Figure 2). At three months (the mid-point of the course) the difference between the mean scores in the two groups was not significant (P=0.631). At the end of the course the mean depression score in the study group was significantly lower (P=0.046) than the control group (Figure 2). The mean scores for depression decreased over the 4 assessments. This tendency was significant in the assessment group (P=0.003) but not in control group (P=0.689).

Figure 2: The mean depression scores and standard errors of the means (SEM) for a control group and a study group of doctors with pre-existing signs of depression, assessed twice before, once during and once at the end of a six-month course in Adaptation Practice.

Stress

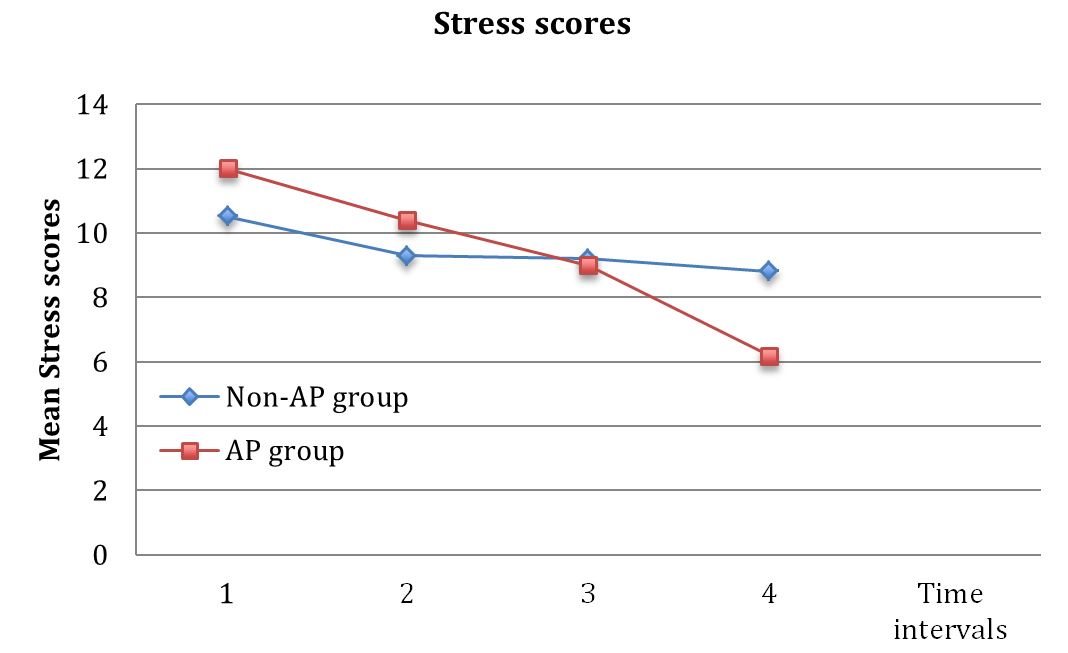

There were no significant differences between the control group and the study group either one month before the course started (P=0.234) or immediately before it started (P=0.505). The stress scores were all greater than 8 (Figure 3). At three months (the mid-point of the course) the difference between the mean scores between the two groups was not significant (P=0.621). At the end of the course the mean stress score in the study group was lower (P=0.077) than that of the control group (Figure 3). The mean assessment scores for stress decreased over the 4 assessments. This decrease was significant for the assessment group (P=0.001) but not for the control group (P=0.425).

Figure 3: The mean stress scores and standard errors of the means (SEM) for a control group and a study group of doctors with pre-existing signs of stress, assessed twice before, once during and once at the end of a six-month course in Adaptation Practice.

Correlations

At all four assessments there were correlations among all three psychological parameters. At the initial assessment the correlation between anxiety and depression (r2= 0.405; P = 0.029) and between depression and stress (r2= 0.800; P < 0.0001) were significant but the correlation between anxiety and stress was not (r2= 0.253; P = 0.185). At the commencement of the course the correlation between anxiety and depression (r2= 0.479; P = 0.009), between depression and stress (r2= 0.765; P < 0.0001) and between anxiety and stress (r2= 0.486; P = 0.007) were all significant.

At three months (the mid-point) the correlation between anxiety and depression (r2= 0.526; P = 0.003), between depression and stress (r2= 0.622; P < 0.0001) and between anxiety and stress (r2= 0.790; P < 0.0001) were all significant and similarly at the and of the course: the correlation between anxiety and depression (r2= 0.604; P = 0.001), between depression and stress (r2= 0.577; P =0.001) and between anxiety and stress (r2= 0.740; P < 0.0001) were also all significant.

Assessments of the doctors’ psychological states and methods of coping

The doctors attending the course were assessed individually in private. They variously complained of stress, anxiety and depression. Notable findings included suicidal thoughts, plans for suicide, self-medication, excessive consumption of alcohol and an intention to leave the medical profession because of the unbearable pressures involved.

By the end of the course all these signs and symptoms had improved and the doctors felt confident in their ability to cope not only with pressures from outside but also with emotion, moods and feelings inside. One doctor still wanted to leave the profession but less adamantly than before, and stayed.

There was no qualitative assessment of the control group.

Qualitative Self-assessments

The anonymous self-assessment reports give meaningful, subjective accounts of what the doctors experienced individually. They fall into four main themes. There were no negative comments.

Connecting with emotion physically in the body

The following comments indicate contact with emotion:

‘I am more aware of my feelings.’

‘It is difficult to say “Yes” to unpleasant or upsetting feelings and situations. I have always preferred to avoid them and I have had a lifetime of suppressing emotions, so it is very difficult to say “Yes” to them, but this is what I am now doing.’

‘Since I’ve been more aware of my feelings there has been an enormous improvement in concentration.’

Developing inner emotional strength and coping.

A number of comments indicate the need to develop the strength to contain emotion physically in the body:

‘I am more accepting of daily stresses at work.’

‘I try to deal with problems instead of feeling so desperate and so wronged by them.’

‘I am calmer, and I lose my temper less often and less dramatically.’

‘The Practice was difficult initially because of my own resistances to it.’

‘I’ve always avoided seeking help for myself. I often feel worse than the patients I prescribe antidepressants for. I can now cope and I feel stronger but I don’t feel I’ve been treated and I now realise I didn’t need treatment: I needed to learn what to do and how to do it.’

Dealing with unpleasant, unwanted thoughts.

These comments illustrate the doctors’ new reactions to thoughts as they started to address the underlying emotion that normally drives worrying thoughts:

‘I now have less ruminations.’

‘As a long-standing ruminator I now realise these thoughts are the source of many anxieties. Thoughts were the main problem for me.’

‘I have learned to deal with obsessional thoughts by not giving time to them.’

General well-being.

The doctors commented on their sense of general well-being and ability to cope:

‘I am less tense and less anxious.’

‘I am now coping with episodes of work overload much better.’

‘I am feeling better generally.’

‘This has given me confidence to pursue the course of action I knew was correct.’

‘There are all-round improvements because of adapting myself to work and other people.’

‘I am happier and more content, optimistic and much less negative.’

DISCUSSION

Varying degrees of stress, anxiety or depression are universal.16, 26 Only about half of those thought to be clinically affected by these conditions seek help for them.26 If put into practice, sound medical knowledge and training can be beneficial to doctors’ own health.1, 11, 15 This does not seem to be true for stress, anxiety and depression.22 Too little is known about emotional and psychological problems, and treatment for them is inadequate.2, 9, 15, 17, 19, 21, 23, 28, 29

In this study, there was a high level of interest in how to deal with stress, anxiety and depression. Almost one third of respondents had scores on the HADS and SSS that suggested worrying levels of emotional and psychological problems amongst these working GPs. The fact that 152 doctors (68% of respondents) declared an interest in a six-month evening course (90 minute sessions after work on Thursday evenings) to learn how to deal with these conditions, suggests that:

- stress, anxiety and depression are significant problems either amongst their patients or for the GPs themselves, or both

- GPs are not confident in their ability to deal with them and want to learn more

- although they have a strong tendency not to admit that they cannot cope and not to seek help, doctors are willing to attend a course to train and to learn.11

Most doctors tell their patients to seek professional help and to talk about their feelings but do not do so themselves.3, 5 They prescribe drugs for their patients that either the doctors will not take themselves or that they take but find ineffective. Of the 15 GPs on the course only one had mentioned psychological difficulties to a colleague and one to a partner and both only reticently. 16

ADAPTATION PRACTICE

Adaptation Practice strongly discourages self-disclosure, except in private to the Adaptation Practice teacher, which is necessary in order to assess the nature and severity of any problems and to lay the foundations for a rapport. Adaptation Practice sessions involve detailed discussion of moods and feelings as physical sensations and powerful forces that affect behaviour in all human beings. The ethos in Adaptation Practice is for participants to learn from their own experience how they are affected by emotion and how they can change this by containing themselves and not letting the emotion control them. It is not to criticise, judge, blame or condemn. Consequently, without the causes of stigmatisation, there is no prejudice and no stigma; instead there is respect and dignity and a pragmatic attitude to change.16

Adaptation Practice trains individuals to bear and endure upsetting, disturbing emotion by not expressing it, not suppressing it, not distracting themselves from it and not numbing themselves to it with drugs (alcohol, recreational drugs or prescribed medication). Bearing it this way develops emotional strength and resilience.

The high level of interest, the willingness to attend in groups and the positive results from this study indicate that Adaptation Practice is an acceptable way of teaching doctors how to cope with their own stress, anxiety and depression, that makes sense intellectually and emotionally. This, as well as the pragmatic approach mentioned above, makes Adaptation Practice radically different from other approaches.

GENERAL COMMENTS

Given that those who could not attend asked for an alternative day to attend, gave us reason to assume that the manner in which the study group and the control group were selected – individual availability on a given week night – would not have biased the sampling procedures and it seems reasonable to assume that the two groups did not differ in any meaningful way that would have biased the outcome.

Not surprisingly, there were strong positive correlations between anxiety and depression and between depression and stress on all assessments and between anxiety and stress on all but the first assessment, suggesting a strong association among these parameters of psychological states.

The mean scores for anxiety, depression and stress fell significantly in the participating GPs compared with the control group. The subjective reports from both the medical assessments and the self-assessments support these changes in the study group.

This study begs a number of important questions:

- if doctors are prejudiced and stigmatise mental illness amongst themselves then what are their conscious, or unconscious, attitudes to mental illness in their patients? 3, 5, 9, 24

- if doctors cannot cope with emotional problems themselves then whom are they and their patients to turn to for help? This is not the same as doctors suffering from physical conditions requiring surgery, or medications such as insulin or antibiotics.3, 5 Doctors expect, and are expected, to be able to cope with their emotions and, if necessary, that the treatment they give their patients will also work effectively for themselves

- what are doctors to do and what are their patients to do, when doctors succumb to their own moods and feelings?

Adaptation Practice could be integrated in the medical curriculum at undergraduate and postgraduate levels, including Continuing Professional Development (CPD). Not only GPs but all doctors and other healthcare staff (nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, social workers, etc.) could develop emotional resilience – which the GMC have proposed in recent years – and a better understanding of emotional and psychological problems and mental illnesses.

It is hoped that this preliminary study will stimulate and encourage a new way of looking at and investigating emotional and psychological problems and lead to further evaluation of Adaptation Practice.29, 30

With adequate training doctors and psychologists could teach Adaptation Practice.

|

Acknowledgements We are grateful to a research grant for this study from TRIP (Turning Research into Practice, the evidence-based medicine portal); to Jon Brassey and Chris Price for helping organise the course; to Rex Scaramuzzi, Emeritus Professor, The University of London, Department of Medical Sciences, for the statistics and general advice and support on preparing the report; and to Steven Davey, independent researcher on emotion, for advice and support in preparing this report. Competing Interests Clive Sherlock has taught Adaptation Practice since 1975 Author Details CLIVE SHERLOCK, BM BS, MRCPSYCH, Wolfson College, Oxford OX2 6UD, UK. CHRIS JOHN, MB BS, MRCGP (Retired) Newport, Gwent, UK. CORRESPONDENCE: CLIVE SHERLOCK, Wolfson College, Oxford OX2 6UD, UK. Email: clivesherlock@adaptationpractice.org |

References

- Stanton J, Randal P. Developing a psychiatrist-patient relationship when both people are doctors: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010216. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015- 010216.

- Mathers CD, Loncar D (2006) Projections of Global Mortality and Burden of Disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med 3(11): e442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442.

- Anonymous. Medicine and mental illness: how can the obstacles sick doctors face be overcome? The Psychiatrist. 2012 36: 104-107.

- Garelick A. Doctors’ health: stigma and the professional discomfort in seeking help. The Psychiatrist 2012;36:81-84.

- García-Arroyo J M, Domínguez-López ML. Subjective Aspects of Burnout Syndrome in the Medical Profession. Psychology 2014;5:2064-2072.

- Gibson J, Checkland K, ColemanA, et al. 8th National GP Worklife Survey report. 2015. Centre for Health Economics, University of Manchester: http://research.bmh.manchester.ac.uk/healtheconomics/research/Reports/EighthNationalGPWorklifeSurveyreport.

- Sutherland VJ, Cooper C. Identifying distress among general practitioners: predictors of psychological ill health and job dissatisfaction. Soc Sci Med 1993;37(5):575-81.

- Chambers R, Campbell I. Anxiety and depression in general practitioners: associations with type of practice, fundholding, gender and other personal characteristics. Fam Pract 1996;13(2):170-3.

- Hassan TM, Sikander S, Mazhar N, et al. Canadian psychiatrists’ attitudes to becoming mentally ill. BJMP 2013;6(3):a619.

- Caplan RP. Stress, anxiety and depression in hospital consultants, general practitioners and senior health service managers. BMJ 1994;309:1261-3.

- Branthwaite A, Ross A. Satisfaction and job stress in general practice. Fam Pract 1988; 5(2):83-93.

- Cooper CL, Rout U, Faragher B. Mental health, job satisfaction, and job stress among general practitioners. BMJ 1989;298:366-70.

- Archer J, Regan de Bere S, Bryce M, et al. Understanding the rise in Fitness to Practice complaints from members of the public. Special Report. GMC 2014. http://www.gmc-uk.org/static/documents/content/Archer_et_al_FTP_Final_Report_30_01_2014.pdf

- aillant G, Sobowale N, McArthur C. Some psychological vulnerabilities of physicians. New Eng J Med 1972;287(8):372-5.

- Thompson WT, Cupples ME, Sibbett CH et al. Challenge of culture, conscience, and contract to general practitioners’ care of their own health: qualitative study. BMJ 2001; 323(7315):728-731.

- Stuart H. Media Portrayal of Mental Illness and its Treatments: What Effect Does it Have on People with Mental Illness? CNS Drugs 2006;20(2):99-10.

- Chew-Graham CA, Rogers A, Yassin N et al. ‘I wouldn’t want it on my CV or their records’: medical students’ experiences of help-seeking for mental health problems. Medical Education. 2003; 37: 873-880.

- Harrison J. Doctors’ health and fitness to practise: the need for a bespoke model of assessment. Occup Med (Lond).2008; 58(5): 323-327.

- Fox DM. Commentary: impaired physicians and the new politics of accountability. Acad Med 2009;84(6):692-694.

- Moncrieff J. The myth of the chemical cure: a critique of psychiatric drug treatment. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008.

- Schachter, S., & Singer, J. Cognitive, Social, and Physiological Determinants of Emotional State. Psychological Review. 1962. 69: 379–399.

- Moncrieff, J. The medicalisation of ‘ups and downs’: the marketing of the new bipolar disorder. Transcultural Psychiatry 2014.

- Hidaka B H. Depression as a disease of modernity: Explanations for increasing prevalence. Journal of Affective Disorders 2012;140(3):205-214.

- Weiss MG, Ramakrishna J, Somma D et al. Health-related stigma: rethinking concepts and interventions. Psychol Health Med 2006;11(3):277-287.

- Kirsch I, Moore TJ, Scoboria A, Nicholls SS. The emperor’s new drugs: an analysis of antidepressant medication data submitted to the US Food and Drug Administration. Prevention and Treatment 2002;5: alphachoices.com/repository/assets/pdf/EmperorsNewDrugs.pdf. (accessed 22 Nov 2010).

- Lehmann C. Psychiatrists not immune to effects of stigma. Psychiatric News 2001;36,11.

- White A, Shiralkar P, Hassan T et al. Barriers to mental healthcare for psychiatrists. Psychiatric Bulletin. 2006; 30:382-384.

- Moncrieff, J. & Timimi, S. The social and cultural construction of psychiatric knowledge: an analysis of NICE guidelines on depression and ADHD. Anthropology and Medicine 2013;20,59-71.

- Worley LL. Our fallen peers: a mandate for change. Acad Psychiatry. 2008; 32(1): 8-12.

- Myers MF. Treatment of the mentally ill physician. Can J Psychiatry. 1997; 42(6): 12.

The above article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.